TL;DR: It’s the time of year where security vendors post blog posts with charts of how long it takes to bruteforce a given password. As usual this raised a lot of questions from less security-minded people I know regarding the realism of the numbers, and how realistic the exercise now. As pennace for having generated this data in times past for similar marketing pushes, I will discuss why this is acutally a poor way to teach less-technical users about password complexity; and how users should be creating and using credentials.

What are “time to crack” charts?

Various security vendors over the years have used “time to crack” charts to display the impact of password length and complexity on the perceived security provided by a given password. This is a chart with length of password (ie: 8 characters, 9 characters) on the X-axis, and the character classes present in the secret (password, passphrase) for example: lower case, upper case, mixed case.

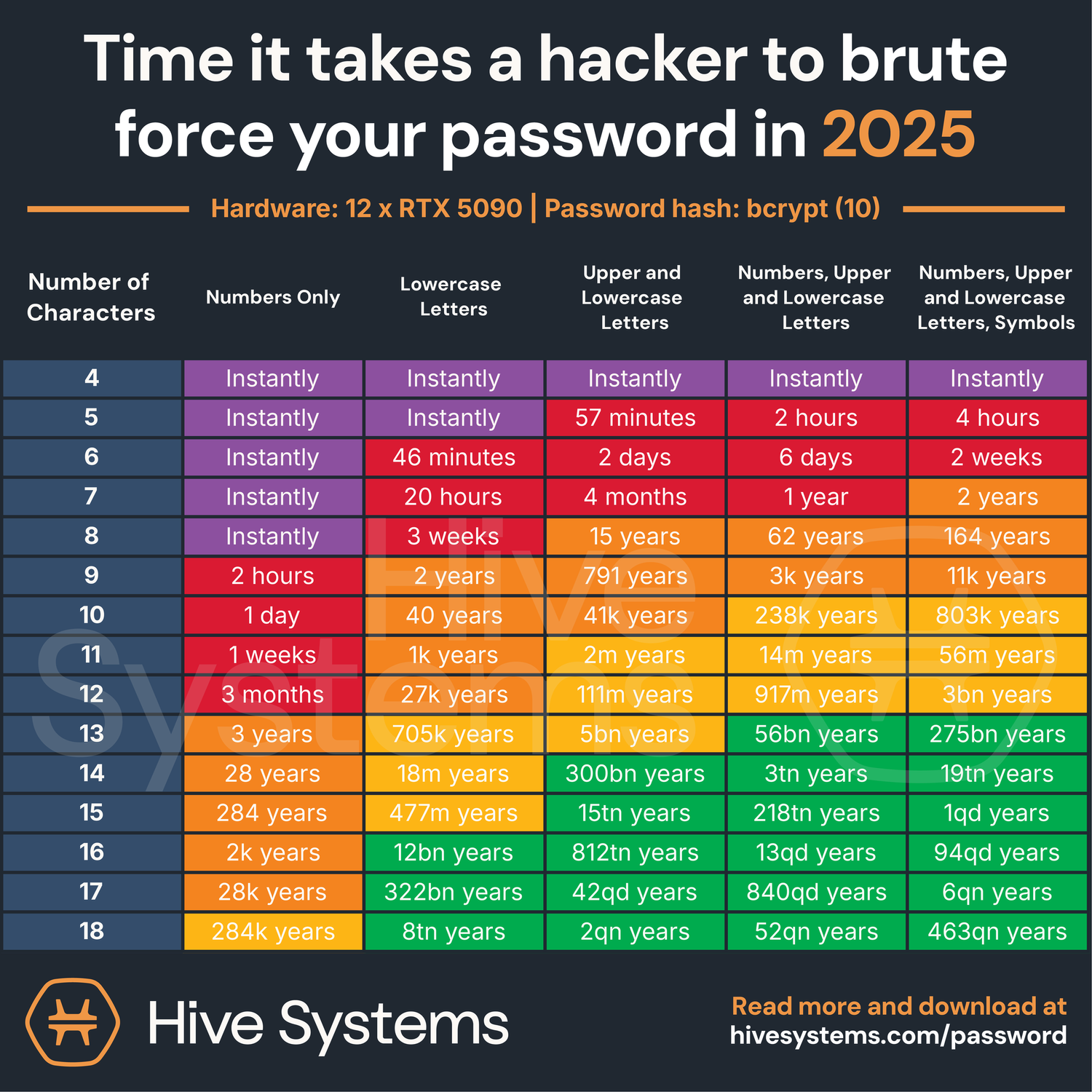

This provides a gradient of “how long it takes to crack the password” (with a naive brute-force attack) for a given length and complexity, with some given hardware (often 8xRTX 4090s, now a number of RTX 5090s). An example of this is Hive Systems’ 2025 password table

So the initial discussion coming from this doing the rounds on the intertubes was largely to the effect of, “that math can’t be right?” of various flavours. The numbers involved in bruteforcing long complex ‘passwords’ ie: plains that are then hashed with the bcrypt algorithm rapidly grow too long for a brain to imagine. It is realistic, the numbers are correct, but they don’t necessarily mean anything to a reader.

So what’s the problem? There are a number of issues with reducing the reality of attacking hashes and providing a given timeline until it’s broken depends on a number of assumptions that make things sound more secure than they are:

- Hackers don’t crack hashes with bruteforce, especially slow algorithms like bcrypt

- A lot of platforms we use in our daily lives do not use secure algorithms like bcrypt, they’re using sha-256; like banks and other various institutions

- Hackers don’t need to crack all hashes, they just need to crack some to get their initial foothold

We’ll cover these individually.

The reality of bruteforcing

An attacker would never attempt to bruteforce any hashes, let alone something as slow as bcrypt. It’s approximately as good a use of sparks as training LLMs is. An attacker will always attempt to use wordlists both of previously leaked passwords such as the ones previously discussed on this blog, n-grams, candidates generated from the target’s corporate sites and public information, dictionaries and so on, combined with a set of rules to manipulate and malform these into new forms, such as password becoming password123.

This is remarkably more effective than bruteforcing which makes it more cost effective. So much as implying bruteforcing is realistic is reductive and misleading towards a user that does not know better. It is simply not the reality, and it’s intentionally padding out the time to attack a given hash.

This leads to a user having an ulrealistic expectation about how secure their account is, and what the realistic threat model is. I’m of the opinion, given the discussions I have had regarding this kind of data (having generated it myself in the past) – it runs the risk of causing a user to believe they’re more secure than they are. If you look at the table, you may believe a 10 character password is safe, while it might be trivially crackable because it’s derived from a simple dictionary phrase. For example you might create a password such as ShrekIsAnOnion2025! believing the chart and accepting that it takes 463qn years to attack, so you should never need to change it, or implement MFA because they’ll never get in. Meanwhile this is a trivial password and would actually take very little time to crack, even as bcrypt. Again, hash crackers do not ever bruteforce (nor do they use rainbow tables – that’s a discussion for a different day though).

Bcrypt vs other hashing algorithms

Security vendors have a vested interest in making these numbers large and surprising in order to improve word of mouth for their advertising campaigns. There’s a reason these go viral every year; big numbers stonks. It also makes it easier to discuss variation in “time to crack” when you can gradient it from instant to billions of years. It’s much harder to develop a cohesive compelling table when working with faster algorithms; a whole table of instant to hours doesn’t grab eyes and makes it harder to develop leads.

The problem is, yes, bcrypt and argon2 are often used by security-conscious developers such as ourselves, however the reality of the industry is that it’s not required. FIPS standard is SHA-256, PCI compliance requires SHA-256. Do you know why security vendors don’t use SHA-256 for these analyses? Because it would go less viral, and the numbers would be less impressive. It is however the industry standard still.

It’s teaching the reader that their passwords are more secure from a bad actor cracking them than they actually are; both from the viewpoint of the reality of how we crack hashes, and the given algorithm’s complexity.

You just need to outrun the other guy

At the end of the day, when you’re looking at it from the viewpoint of a CISO and you’re trying to threat model for your organization and review your security posture, if you don’t have internal training programs, good password rules and enforcement such as a breached password corpus, self-service reset with multiple MFA factors to reduce friction if a user does forget their complex password; the hacker only needs to get one of the low hanging fruit hashes from the users that slip through the gaps. “ActiveDirectoryServerPassword” is just as insecure as “Password123” if the attacker knows what they’re doing.

Conclusion

These kind of reductive time to crack charts make for good marketing to get eyeballs on a security vendors’ products. They however are not a replacement for education, and teaching users what the data actually means. A slow hashing algorithm is not a replacement for MFA, and teaching your users good security hygiene.